Four years later, an invitation to teach at Black Mountain College further elevated Lawrence into the orbit of Josef Albers and the international modernism of the Bauhaus.Īt the same time, in addition to widening his artistic outlook, the 1940s exposed Lawrence to a broadening American landscape. In such standalone and standout paintings as Pool Parlor of 1942, a prizewinner of an “Artists for Victory” competition and purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art that same year, Lawrence already can be seen building on his expanding modernist horizons. These figures included Stuart Davis, Ben Shahn, Jack Levine, and Charles Sheeler. Now that he was exhibiting beyond “uptown,” the Downtown Gallery (which was, by then, located in midtown on East Fifty-first Street) exposed Lawrence to Halpert’s circle of modernist American painters.

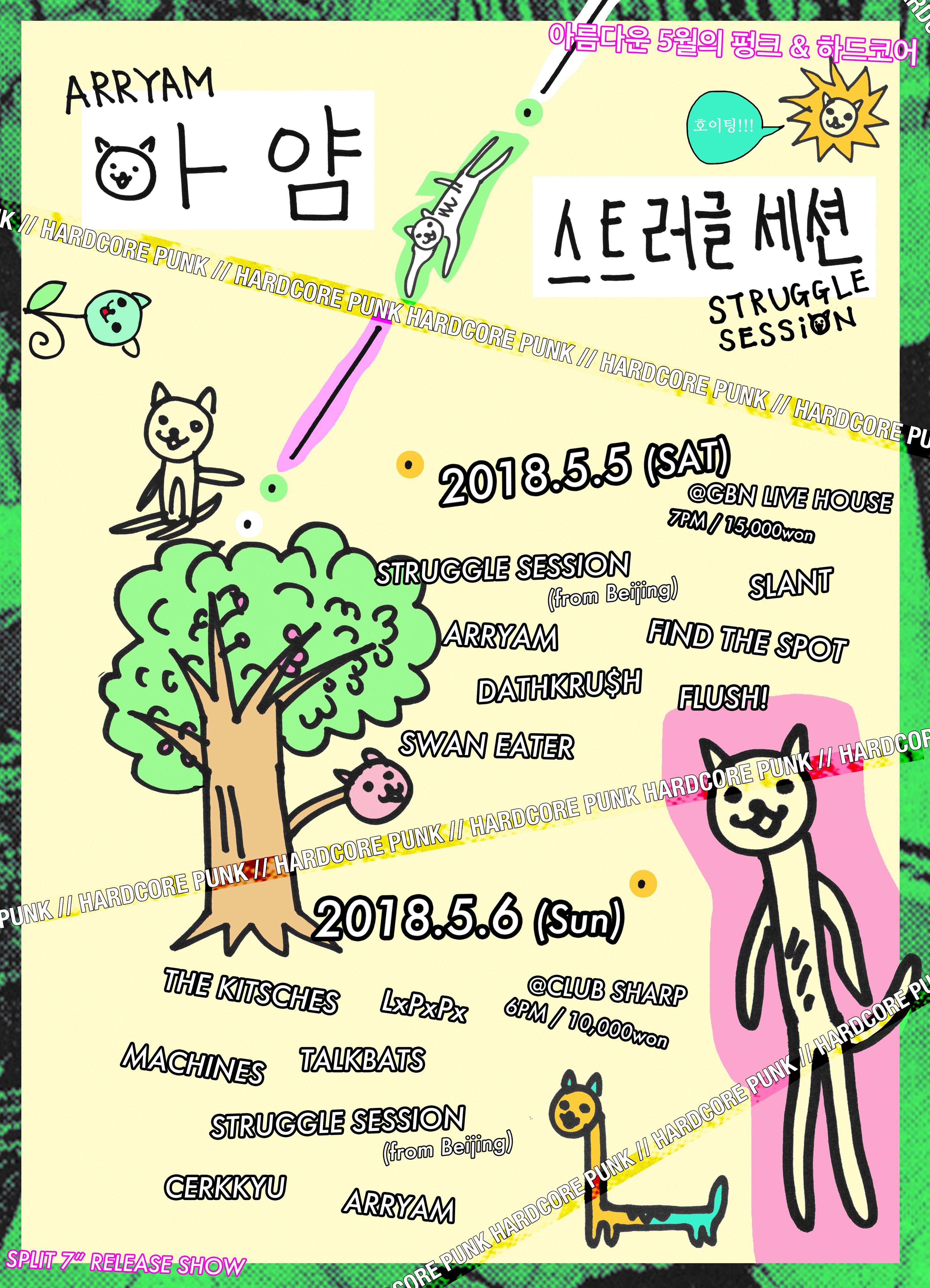

STRUGGLE SESSION EPISODE 100 SERIES

His cycle on “The Legend of John Brown” of 1941, which now exists mainly as a series of twenty-two prints, tells its story more on the surface, without quite the same compositional nuance or absorption.

No other work of such ambitious scope would come quite as easily to Lawrence again.

It was exhibited in the same year he married his fellow Harlem artist Gwendolyn Knight. Painted in a flurry of activity, spread out all together across his Harlem studio, “The Migration Series” connected Lawrence’s personal subject matter with the wandering and restless spirit of modernism. “The Migration Series” connected Lawrence’s personal subject matter with the wandering and restless spirit of modernism. Inspired by the figures of black history, he created narrative portraits of Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and Toussaint L’Ouverture. By the late 1930s, he was already channeling the cosmopolitan worldview of Alain Locke’s “New Negro” into the easel division of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. A child prodigy, he soon apprenticed with Charles Alston, Augusta Savage, and other leading artistic lights of the Harlem Renaissance. Born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 1917, at thirteen he continued the family’s migration north, moving with his mother and sister to Harlem. Lawrence was the product of the same Great Migration he depicted. It succeeds in creating a world, and it holds us in its grip.

There is an extraordinary velocity in this style and an extraordinary empathy. Color is generally somber, yet illuminated by moments of gemlike intensity. Figures are seen as the sum of their actions, never as individualized personalities. Drawing is reduced to the delineation of flat shapes and easily read gestures. Into each image, executed in tempera, gouache or watercolor, is distilled a dramatic episode or emotion of great simplicity, yet the crowded succession of such images traces a complex course. Writing of an earlier reunion, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974, Hilton Kramer noted that The moving power of this dynamic work is revealed every time the series is reunited-most recently in “One-Way Ticket,” the exhibition that was on view at moma in 2015. Lawrence was just twenty-three years old. The odd numbered panels went to Washington’s Phillips Collection the evens went to New York’s Museum of Modern Art. After showing at Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery-Lawrence was the first black American to be represented by a New York gallery-the series was acquired in its entirety through a joint institutional purchase. Sponsored by the Rosenwald Foundation, the series of 1940–41 launched Lawrence from the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library, where he conducted his historical research, to national acclaim. Accompanied by Lawrence’s tightly researched narrative, which supplies the title for each panel, the distilled forms tie the compositions together while connecting the episodes into a unified and abstracted whole.

Painted all at once, color by color, the episodic panels present the early twentieth-century movement of black Americans from the rural South to the industrial North as a puzzle of dynamic shapes and vibrant hues. W here could Jacob Lawrence go after “The Migration Series”? Lawrence’s trailblazing work of sixty paintings, originally called “The Migration of the Negro,” pulled together the story of the Great Migration into a visual American epic.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)